Experience is unitary—my experience is always one. Everything I am conscious about appears within one unified experience and therefore no part of my experience is truely independent from the rest. This is one of IIT’s starting points, the axiom of integration.

Every axiom in IIT has a corresponding postulate that formalizes a requirement for a physical substrate of consciousness. The logic here is that any characteristic feature of phenomenology must be reflected in its physical substrate. For example, if our experience is unitary, or integrated, its physical substrate cannot be composed of two or more completely independent systems. Being “integrated” is thus a necessary requirement for any physical substrate of consciousness. But what does that mean and how do we evaluate it?

The integration postulate according to IIT

According to the IIT formalism (Oizumi et al., 2014), a system is integrated if any unidirectional partition of the system into two or more parts will make a difference to the system’s cause-effect structure. A unidirectional partition means that we eliminate all causal dependencies from one part of the system to the rest but not necessarily vice versa.

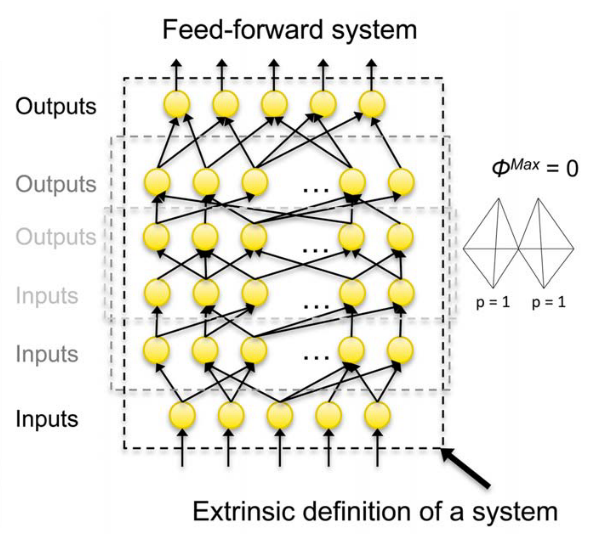

A consequence of formulating the integration postulate in this way is that feedforward systems are excluded from being physical substrates of consciousness. This is because in a feedforward system the upstream parts do not depend in any way on the more downstream parts: layer n does not influence layer n-1 (or any previous layer) at all. Eliminating the dependencies from layer n to n-1 does not make a difference, since there are no causal dependencies in the first place. The feedforward system can thus be partitioned unidirectionally without loss, which means \(\Phi = 0\). It follows that being strongly connected, or recurrent, is a necessary (but not sufficient) requirement for being integrated.

Note that this is directly in line with the integration axiom as formulated above: no part of my experience is truely independent from the rest. In a feedforward system, however, any upstream part is completely causally independent from the more downstream parts. To the extent that the content of a system’s experience somehow depends on the activation states of its components, a feedforward system thus cannot account for an integrated experience.

Why causal integration?

One thing I smuggled in here is that IIT cares specifically about causal dependencies. From a purely information theoretical perspective, layer n-1 in a feedforward system may well correlate with layer n, which means that the mutual information between these two layers is nonzero and mutual information is a symmetric measure (if layer n has x amount of mutual information about layer n+1, the same is true vice versa). Moreover, the various layers of a feedforward system may jointly perform a particular function and, as highlighted by the recent discussion about the unfolding argument, any input-output function can in principle be implemented by a feedforward network (see my commentary here).

Couldn’t we formulate the integration postulate based on information more abstractly, or maybe in functional terms (as recently suggested in Hanson & Walker (2019))?

The first thing to clarify here is that the unity of experience is not the same as “multi-sensory integration”. We are not trying to capture a convergence of information to perform a certain task. Instead, what we want to account for is that all the various parts of our experience are integrated into one whole. This gets confused sometimes.

The reason we care about causal dependencies between system components in IIT is that consciousness is observer independent, while information and function typically are not. Information, in an abstract sense, does not exist by itself; my consciousness does. Similarly, a system is not directly aware of its input-output function. External behavior is exactly that: external to the system, and only relevant with respect to the environment. Intrinsic existence is another axiom/postulate of IIT.

For information to be meaningful to the system itself, it has to be able to make a difference to the system and thus needs to be physically implemented. We have to assess what is meaningful for the system from the intrinsic perspective of the system itself. For example, standard information measures are typically computed using an “observed distribution” of system states. However, any kind of summary distribution across multiple system states is not intrinsic. Nothing in the system’s here and now corresponds to such an average distribution of itself. What is there, in the here and now, is ultimately only the system’s internal mechanisms in their current state. Functionally equivalent systems can have very different internal mechanisms and thus specify different intrinsic information about themselves, as I have discussed in a recent publication. This is why implementation matters for consciousness.

Back to integration: A system is integrated, according to IIT, if its mechanisms constrain each other. In that case, the system constrains itself and exists above a background of external influences. It can be viewed as a partially autonomous entity (Marshall et al., 2017). A feedforward network, however, is never independent of its environment and thus ultimately cannot form an entity in itself. Any borders drawn around it are extrinsic, specified by an external observer (see the image taken from Oizumi et al. (2014), Fig. 20). A system that does not exist by itself cannot be a physical substrate of consciousness. These “pretheoretical” notions are what informed IIT’s formulation of the integration postulate in mathematical terms (and not the other way around; see also Negro (2020) for a related case against “integrated” feedforward systems).

Empirical evidence against feedforward structures

IIT’s formulation of the integration postulate, inferred from the properties of our own experiences, also explains various empirical observations: neurons that have purely afferent or efferent connections to the cortex do not seem to contribute directly to our experience. Visual experiences, for example, do not directly correspond to the activity of retinal neurons, as vivid visual experiences are possible during imagination, hallucinations, and dreams. Moreover, in binocular rivalry experiments, both images are “represented” on the retina, while we are only conscious of one.

What is more, recording the activity of cortical neurons (which means creating a feedforward connection) does not seem to alter our experiences. You don’t become conscious of the processes within the fMRI machine while you are lying in the scanner. Likewise for brain stimulation. This might sound silly, but note that, for instance, the mutual information between the fMRI recording and the brain being recorded can be very high.

Case closed? Maybe not 100%. However, I hope that it became clear that accounting for our integrated phenomenlogy takes more than convergent pathways. Any proposal on how to reformulate the integration postulate needs to address the issues outlined above.