Recently, a paper titled “The unfolding argument: Why IIT and other causal structure theories cannot explain consciousness” by Doerig et al. (2020) created quite a splash in the consciousness community. The paper made the strong claim that causal structure theories, which include IIT, are either false or outside the realm of science.

The argument

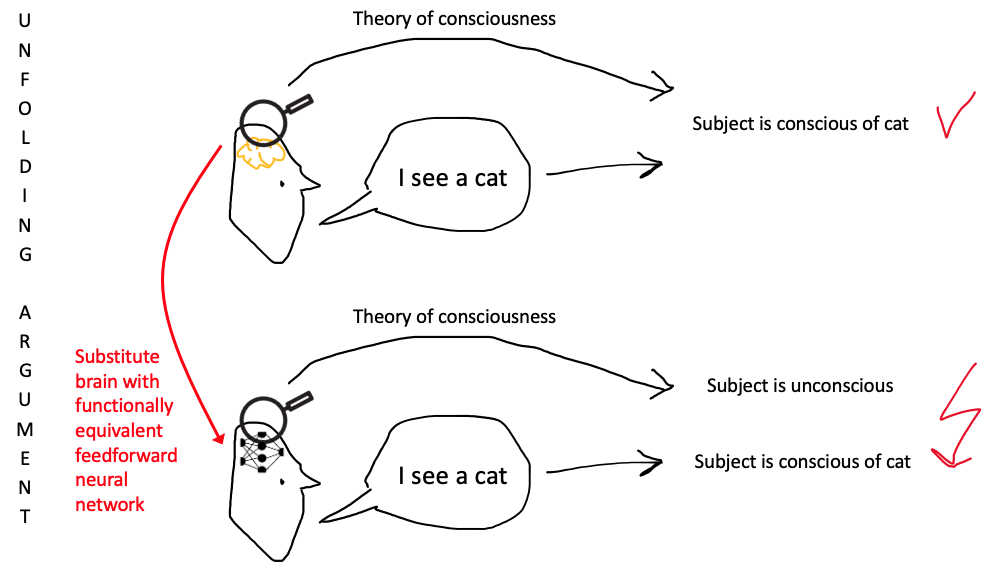

The unfolding argument is based on the fact that any recurrent network can be “unfolded” into a functionally equivalent feedforward network (at least to an arbitrary degree of accuracy)*. This means that—in principle—we could replace the brain of a test subject with an artificial feedforward neural network in any experimental design to test a theory of consciousness. I have drawn a little cartoon to summarize the issue.

Any theory that says that feedforward networks cannot be conscious (such as IIT, see Oizumi et al., 2014) will (ideally) match the subject’s report before their brain got substituted, but not after, even though the subject’s behavior stayed 100% the same. Moreover, we have to go by the report, because what other means could we have to infer the subject’s level of consciousness in a theory-independent manner than the subject’s report? Since such a substitution is always possible (in principle), any theory for which implementation matters is supposedly either false or untestable.

[* Guess who introduced this issue? Functional equivalence is discussed at length in Oizumi et al., 2014 and also in Albantakis et al., 2014. To cite: “Note also, however, that any task could, in principle, be solved by a modular brain with \(\Phi=0\) given an arbitrary number of elements and time-steps.”]

Replies to date

A bit more than a year later, several replies have been published, which have pointed out various issues with the unfolding argument and the conclusions drawn by its authors.

As discussed by Tsuchiya et al., 2019, the unfolding argument advocates a rather extreme form of methodological behaviorism. Clearly, we can empirically distinguish the feedforward neural network from a real brain by looking inside the subjects’ heads and we are allowed to use that knowledge in our inference. There is no reason to treat the two subjects as black boxes. The assumptions on which the argument is based thus do not accurately represent the reality of experimental research on consciousness.

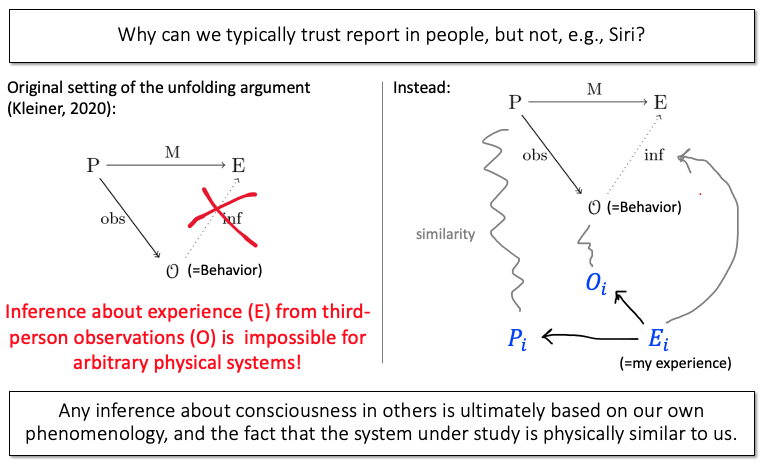

However, as shown by Kleiner & Hoel, 2020 the unfolding argument can be extended to a more arbitrary set of observations used for inferring consciousness. Kleiner and Hoel formalized the unfolding argument in mathematical terms and also rebranded it the “substitution argument.” The crucial requirement is “the independence between the data used for inferences about consciousness (like reports) and the data used to make predictions about consciousness” (Kleiner & Hoel, 2020).

Properly formalized, it turns out that according to the unfolding/substitution argument, falsification is an issue for all theories of consciousness that rely “non-trivially” on physical systems (which is argued especially well in Kleiner, 2020). This includes “Global Neuronal Workspace Theory, Higher Order Thought Theory and any other model of consciousness which is functionalist or representationalist in nature”, except for strict input-output functionalism. To the extent that the original unfolding argument put forward by a group of functionalists was a shot at discrediting IIT in particular, one could now quip that it backfired.

Addressing the argument from a different angle, the notion of falsification advertised in the original publication (Doerig et al., 2019) has been criticized as overly strict (Negro, 2020). Moreover, Negro nicely points out that there are valid pre-theoretical reasons to exclude feedforward systems from being conscious, in an argument that parallels Ned Block’s “Blockhead argument” (Block, 1981).

Finally, it should be pointed out that the proposed substitution with a feedforward network is not practically possible in the case of the brain, as the feedforward network would have to be giant, constituted of many more neurons than the actual brain. Indeed, we have shown that there are evolutionary reasons why we are not a feedforward neural network (Albantakis et al., 2014). However, the unfolding argument does not depend on the practicality of the substitution, it only requires that it is possible in theory. Hanson and Walker (2019) have also shown that for certain (small) networks it is possible to substitute them by a feedforward network with the same number of neurons, but that does not add anything further to the unfolding argument.

So do we have to draw the dire conclusion that consciousness is in fact outside the realm of science and all efforts to date have been a huge waste of time and effort? No. Actually, the fact that we have made considerable progress in the scientific study of consciousness over the past decades, including the development of novel paradigms that contrast experience and report, should make us somewhat skeptical about the validity of the unfolding/substitution argument. Nevertheless, I think the foremost reason why the unfolding/substitution argument is flawed has not been made sufficiently explicit yet.

Why the argument is a non-starter

There are two ways the unfolding argument may play out: (1) we accept report as our basis for inferring consciousness, then causal structure theories are falsified (see my sketch above), (2) we do not accept report as an indicator of consciousness, then we find ourselves outside the realm of science. However, this is a false dichotomy. Not all reports are the same when it comes to inferring consciousness.

In short, consciousness cannot be studied or tested in systems that are physically very different from us, because without a theory we have no way to tell.

Here is a simple example: Would you trust Siri (or Alexa for that matter) if they claimed to be conscious? I’m pretty sure you would at least have some doubts about such a claim. On which basis then can we decide whether your smart phone is conscious or not? [Insert your favorite indicator of consciousness]? Why? The problem is that we actually have no theory-independent way to tell whether any arbitrary physical system is conscious or not.

[Note that this is not just a property of consciousness. The same issue arises, e.g., with notions such as “being alive”. The crucial difference between life and consciousness, however, is that what we call life is in fact nothing but whatever set of properties we define it to be, whereas phenomenology is directly observable (see below) and thus cannot be explained “away” in the same reductionist manner. Consciousness as the explanandum, what we want to explain, is not a function of the brain (even if the explanans might be in the end). To be conscious is to have an experience, to exist for oneself.]

What about intuition (see for example Aaronson (2014) whose intuitions supposedly falsified IIT long before the unfolding argument)? Since consciousness is not directly observable in others (from a third-person perspective), we do not have intuitions about consciousness. Our intuitions are always about (intelligent) behavior only and thus of no use for identifying conscious systems.

But here comes the crux: consciousness is directly observable by the experiencer. I can observe my own; I experience it and I can introspect on it; I just cannot directly measure it in others. Now, the only reason that I can study consciousness in others (e.g., other humans and possibly animals) is their physical, structural similarity to me.

I have tried to capture this point in a semi-formal diagram, based on the one drawn in (Kleiner, 2020) to depict the unfolding argument. A model (theory) of consciousness (M) makes a prediction about the experience (E) of a physical substrate (P). In order to test the model, the prediction is then compared to an inference about the system’s experience from a set of empirical observations (O), which indicate report or behavior more generally. However, such an inference is not actually possible for any arbitrary physical system. Instead, a theory-independent inference ultimately has to be grounded in “my own” (or the experimenter’s) phenomenology. This is reasonable (albeit never perfect) if the system under study is physically similar to me (the experimenter).

[Note that one could argue that instead of physical similarity, we could base our inference on functional similarity. However, physical similarity only implies that consciousness is somehow related to a physical substrate, which includes the possibility that consciousness is functional, whereas using a purely functional similarity already presupposes that consciousness is functional in nature. In the latter case, theory and inference would not be independent.]

For the unfolding, or more generally, the substitution argument, this means that once the subject’s brain gets replaced by an artificial system with very different physical properties, the subject’s report cannot be used to infer consciousness. Therefore, this scenario is not suited to falsify a theory of consciousness.

However, there still are plenty scenarios left under which we can sufficiently trust the subject’s report. Whenever the subject shows similar behavior to my own and is physically similar to me, I can rely on my own experience to infer the experience of the subject based on their report.

As an example, take sleep as a common experimental condition to study consciousness. It has been suggested that the reason we compare wakefulness and sleep to study consciousness “is based on the premise that outward behavior is an accurate reflection of internal subjective experience” (see Jake Hanson’s blog post). This is decidedly not the case. After all, we distinguish between dreamless sleep and dream experiences, and one of the most interesting new developments in the experimental study of consciousness is a within-state paradigm that compares these two conditions (Siclari et al., 2017). Yet, from the outside, there is no difference. For emphasis: sleep is interesting with respect to consciousness solely because we all seem to lose our consciousness every night in deep sleep, whereas dreaming is very similar to wake by our own experience.

Another important point to make here is that our inferences about consciousness are not deductions. They are never perfect and are not beyond any doubt. In the case of sleep and dreams, for example, memory is always a confounder. What we rely on instead are inferences to the best explanation. Through painstaking experiments, including studies on lucid dreaming, we can now be pretty sure that our dream content is based on very similar neural activity as wake experiences and not confabulated upon wake.

Are there still problems with report even if we rely on healthy adult human subjects? Yes, indeed. Some predictions may be hard to test even in humans. For example, IIT’s prediction that inactive neurons may contribute to shape the content of an experience while inactivated neurons may not (Oizumi et al., 2014), is hard to test directly based on similar consideration as the unfolding argument. However, there are plenty of approaches to distinguish a theory of consciousness from a theory of report.

How should we proceed? Inference to the best explanation!

I will quote from the scholarpedia entry on integrated information theory: A theory of consciousness “must first be validated in situations in which we are confident about whether and how our own consciousness changes … . Only then can the theory become a useful framework to make inferences about situations where we are less confident”.

To that end, we should work on devising new ways of testing theories of consciousness that are compatible with straightforward, reliable reports (for example, based on prolonged visual stimuli, the structural equivalence of predicted and reported experience, the spatio-temporal scale of consciousness (see also Tsuchiya et al. (2019), Tononi (2015) and Tononi et al. (2016))).

Will that be enough? Will we ever be able to sufficiently constrain our working theory of consciousness such that we can confidently apply it to judge systems that are very different from us? Well, that remains to be seen, but I would argue that there is still plenty of constraining that can be done for now.