By now we are fairly certain that our conscious experiences arise from within our brains and that the content of these experiences somehow has to do with neurons firing and interacting in specific ways. Empirical studies of consciousness are thus conducted under the banner of neuroscience, anesthesiology, and neurology. Occasionally, renowned physicists become interested in the problem of consciousness (e.g., Tegmark (2015)), but their contributions are typically philosophical in nature. It may be premature to try to connect consciousness to the (micro) physical. However, by focusing exclusively on brains, neuroscientists often forget one of the biggest problems in studying consciousness: that every person has their own.

The individuation problem of consciousness

One of the easiest ways of testing a theory of consciousness is to apply it to a room full of people — 5 awake adults let’s say. If the theory cannot identify (at least) five consciousnesses there is a problem. Yet, almost no proposal to date has the theoretical tools to approach this problem without presupposing brains as the seats of experience (IIT being a notable exception, see also Fekete et al. (2016)).

Crucially, causal analysis is the only way to address this individuation problem as I will argue below by means of a thought experiment inspired by Searle’s Chinese Room Argument. The reason is that identifying individuals in general requires intervening upon the system under study. The implication is that no theory of consciousness can do entirely without assessing causal structure. Pure functionalism is out.

[In this way, the current post takes another stab at clarifying inconsistencies in the recent discussion about the unfolding argument, see my earlier commentary here. A related point was made by Kleiner (2020), arguing that all theories of consciousness (should) depend non-trivially on physical systems.]

The Greek Cave argument

From the outside the setup of my though experiment is identical to Searle’s. For a change though, let’s imagine a cave in the Greek mountains: travelers can ask any question they want to the cave (a black box), written or spoken, does not matter, but it has to be in Greek. They will then receive an answer from within the cave, also in Greek.

In the original Chinese Room setup, the questions are answered by a person who does not speak a word of Chinese but is able to perform the task by looking up the correct answer to any given question from a giant look-up table. The conclusion drawn by Searle is that true understanding doesn’t necessarily come along with the ability to perform a certain function. Therefore, the Turing test is inadequate.

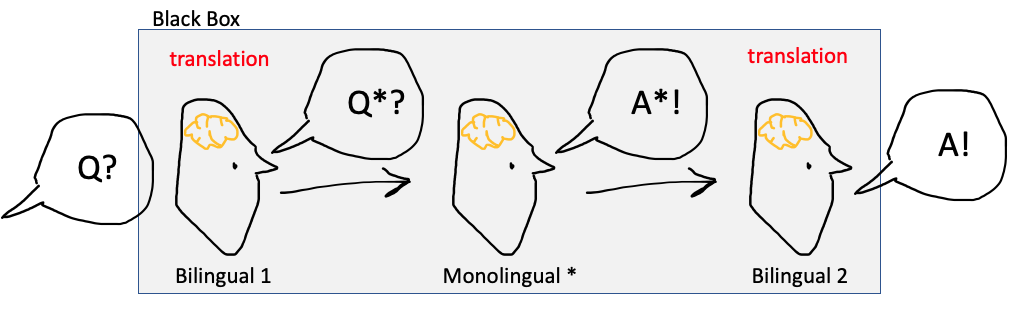

In the Greek Cave, there also is a person that does not speak a word of Greek. However, the way the questions get answered is different. Looking inside the Greek Cave (see sketch below), we find three people. One, a Greek-English bilingual, receives the question and translates it for the English monolingual. The monolingual answers in English. This answer is then translated back to Greek by a third person, also a Greek-English bilingual.

[To be technical, the third person should not be able to hear the first one. However, it is not crucial for the argument that the interaction is unidirectional only. For example, it would be OK for the monolingual to ask clarifying questions to the first person. Also, we should assume that no person in the cave knows the actual setup.]

[Note also the analogy to sensory inputs and motor outputs in the brain and the question whether they contribute to the experience, or where the actual neural correlates are located.]

Clearly, the Greek Cave can pass the Turing test. By contrast to the look-up table in the Chinese Room, in the case of the Greek Cave there is no doubt its implementation is possible in principle. From the outside it looks as though someone is understanding and answering the questions in Greek. Here is the point: no one actually answers any question in Greek; no one has the conscious experience of answering questions in Greek; and it would be wrong to conclude that a conscious being must have performed the task.

To emphasize this last point: all three people are necessary to perform the task. The function of answering questions in Greek is distributed across the three individuals. While answering questions in Greek is certainly indicative of consciousness in humans, it is not sufficient in case of a black box. The cave as a whole is not conscious (but see below).

One may object that we could still conclude that somewhere inside the cave there is at least one conscious being. Maybe. Maybe not. But what if the third person falls asleep? Should we then conclude that nobody is home? Also, in the end our goal is to say something about the quality of the experience. Yet, no one in the cave experiences answering the submitted questions in Greek. The only “being” that could have those experiences would be the system of all three people jointly.

We can conclude that performing the same (complex) function can come associated with very different experiences and be split into different numbers of consciousnesses (possibly including zero, but that does not follow directly from this thought experiment).

What if we had a joint recording of the brain activity of all three people in the Greek Cave?

As a possible objection, a machine-state functionalist might argue that we can map the brain states of the English speaker in the middle onto those of a Greek speaker answering the same questions, maybe not perfectly but close enough. We can thus identify the middle person as the minimal functionally equivalent system, granting them a consciousness of their own. Fine. But there must also be a possible mapping of the three-people system, which after all is actually performing the task. If that gets excluded, functional equivalence is insufficient by itself.

Moreover, we can imagine a person who knows Greek pretty well, but is not fluent. That person may first translate the question into their native language. Then think about the answer in, e.g., English, and translate it back. The difference to the Greek Cave scenario is that now, the experiences of translating and answering happen within one consciousness, yet there might be a more minimal functional kernel which may be mapped onto the states of a Greek person answering.

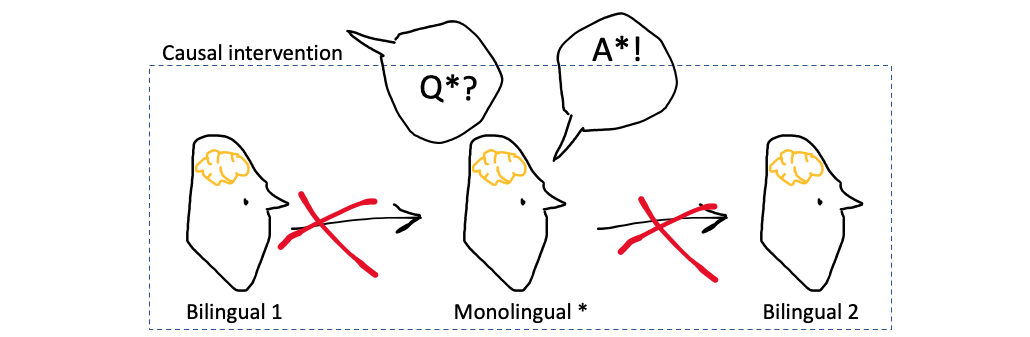

Identifying three conscious people in the cave requires perturbation

Of course, there is an easy way to identify the three people if we can access the cave: we just talk to each of them directly. However, for each one, we have to modify their inputs and/or outputs, which means that we have to perturb the system into states that it otherwise would not take. For example, we would have to query the English monolingual in English to get reasonable answers (see figure below).

Interacting directly with the people inside the cave corresponds to perturbing the system, which amounts to causal analysis and may vary with implementation.

In the absence of predetermined boundaries, we can only fully understand a system by assessing what each element is capable of in isolation and in combination with any other subset of the system. This is exactly what the IIT algorithm is based on: perturbing the system in all possible ways. Systems that map onto each other considering all the various ways in which they can be perturbed are causally identical and thus will have the same value of integrated information.

The Greek Room argument may not be detrimental to every variant of functionalism (I would be happy to receive comments in this regard). However, I would conjecture that those flavors of functionalism that survive the argument implicitly contain some notion of causal structure.

Finally, we can of course avoid the above conclusions by accepting that the cave (or the system of three people within it) is in fact conscious. Yet, the individual consciousnesses surely remain and would also have to be account for.