What is reality? What an important and difficult question. How odd: the more basic the questions, the more difficult the answers. What is life? What is a table? What is circular? How does time pass? What is a person? What is possible? Metaphysics tries to answer some of these questions, while physics tries to answer some humble version of “What is reality?” In mathematics, “What is a set?” is a very basic question, which is nonetheless difficult to answer, as the natural definition of a set is problematic due to self-reference and negation, as we will see below.

I have been working as a physicist for many years, yet I must respond to “What is reality?” with “I don’t know”. I only know that reality is not only weirder than we suppose, but weirder than we can suppose, paraphrasing Haldane’s quote.

To illustrate the weirdness of reality, let us consider a case in point: quantum physics. According to quantum theory, physical properties of objects (such as position or color) need not be well-determined, but can be in a superposition. This superposition is destroyed when the property is measured, and that is why we only seem to observe well-determined properties—a color, a position, a velocity… Superposition means something like mixture, but it is a special mixture, which unfortunately I can only define mathematically, partly because I only understand quantum mechanics mathematically.

Imagine a sock with a quantum color, so that it can be in a superposition of blue and pink. Upon measuring the color, this becomes suddenly well-determined, and we observe, for instance, blue. If we prepared the same superposition again, we would observe, perhaps, pink. Quantum mechanics predicts the probability of obtaining each result, provided we know the initial superposition of blue and pink.

Imagine a pair of socks whose color is quantum, so it can be in a superposition of pink and blue.

As you can see, the measurement process by which the superposition suddenly “collapses” is very weird, and in fact it is problematic.

The superposition principle can also be applied to composite systems, and gives rise to entanglement. If we had a pair of socks with a quantum color (pink or blue), these could be in a superposition in which both are blue or both pink. This is even weirder, as I could separate these socks, leaving one in Innsbruck and sending the other to Jupiter. If I measured the sock in Innsbruck and obtained blue, I would immediately know that the sock in Jupiter is blue. So I would have learned a property of an object of Jupiter (the color of a sock) without any signal travelling from Jupiter to the Earth.

If you find this crazy, you are not the first. Many thinkers did not want to accept it. Einstein, Podolsky, and Rosen, for instance, thought: We are surely forgetting something, some hidden variable which, if included in our description, would turn the superposition into a mere mixture of ingredients. This mixture would describe your lack of knowledge of the state of the system, instead of a fundamental property of the physical system: The socks would be pink or blue, but you would not know the color—you would only know that with a certain probability they are pink, and with another they are blue. This mixture is not mysterious at all, for it is akin to you trying to guess which socks I am wearing today. I only have blue and pink socks, and half of the days I wear the pink ones, and the other half the blue ones. Moreover I always wear matching socks. If you see that my left sock is blue, you immediately know that my right sock is blue, without a signal travelling from my right foot to you. This would also hold true if I had fantastical legs with my left foot in Innsbruck and my right foot in Jupiter. There is nothing mysterious here: the color of my socks is well-determined, and the only problem is that you don’t know it. Hidden variables would let us turn the superposition into a mixture, and remove the mystery of quantum mechanics.

In the 1960s Bell transformed this discussion into a falsifiable prediction: He showed that if physical reality were described by a non-mysterious mixture, an observable quantity could be at most 2, whereas with superposition this quantity could be greater than 2. This quantity was measured in the lab, and it turned out to be greater than 2! Myriad experiments have been performed since then, each more precise than the other, or ruling out alternative explanations such as paranoid scenarios where the socks communicate with each other, or the detectors conspire to hide certain results. And the result is: This quantity is more than 2. It follows that hidden variables cannot explain the observations of quantum physics. This amazing story about superpositions is thus our best explanation of reality.

The predictions of quantum physics are incredibly successful: they have so far passed all experimental tests. Yet, the most fundamental question remains open, at least for me: What is a superposition? We do quantum mechanics in our daily lives, theoretically and experimentally, disagreeing on whether we live in just one universe or in countless copies of what seems to be this one universe. I find this a colossal disagreement—we can disagree on how to organize our society, on ethical questions, on when we will contact life on other planets… But not knowing whether there are infinitely many copies of myself, or just one! How can we live like that?

A fascinating feature of physical reality is the power of abstraction: many aspects can be wonderfully described with relatively simple mathematical models (this is much less so in biology, where things are too difficult). Why? I don’t know. I also don’t understand the metaphysical part of this question: Do these abstractions exist somewhere? They clearly do not exist in the physical world, as there is no circle whose perimeter divided by its diameter be \(\pi\). If we define the number three as the equivalence class of all things of which there are three (three oranges, three cars, three planets, three ideas), does the number three exist somewhere? We again find that the more basic the questions, the harder they are.

Following these brushstrokes on (quantum) physics, let me share with you a somewhat poetical idea: for me, reality is a limit. To explain this idea, imagine a sequence that never ends, that is, that does not have a last element. This is the case, for example, if every element of the sequence is tagged with a natural number: the first element has tag 1, the second has tag 2, the third, tag 3, etc. Since there always is a following natural number, the sequence never ends. And since there is no last element, the amount of new things that may appear during the sequence is unbounded.

A sequence has a limit if it gets as close as possible to something, and this something is the limit. For instance, the sequence 1,1/2, 1/3, 1/4, 1/5, … has the limit 0. Notice that it never reaches 0, but it gets arbitrarily close to it. Infinity can only be defined as a limit—for instance, as the limit of the sequence 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 … Infinity is thus not an incredibly large number, but a limit. A googol, 10100, is infinitely far away from infinity, and so is any other ridiculously large number.

In general, the limit cannot be guessed from a finite number of cases—one would need to invoke a hypothesis about the entire sequence, but this is out of reach for a finite number of cases. This is, in essence, the problem of induction. The limit is thus, in principle, unreachable, inaccessible.

Well, the idea is that for me, reality is a limit: Something that offers new surprises, new landscapes, new energy regimes, new physics, new possibilities without end. This may sound pessimistic, as it implies that reality is unreachable, for we are finite. But, on the contrary, for me it is a message full of hope, as it implies that what can be discovered has no ceiling. This message fills us with humility, but also with power—the transformative power of knowledge. In the words of David Deutsch, we are at the beginning of infinity, and we will always be. Compare what we know now with what we knew 100 years ago, and now imagine what we will know in 100 or 1000 years (if we still exist). If we are now at the beginning of infinity, in 100 or 1000 years we will also be at the beginning of infinity—one cannot reach infinity.

That reality is a limit is my way of expressing that I don’t think that full knowledge of reality can be reached. I don’t even think that we can imagine the amount of possibilities it offers. We know a great deal about its marvels, but we are only at the beginning of infinity. In the words of Popper, our knowledge can only be finite, while our ignorance must necessarily be infinite.

Note that the mathematical definition of limit is almost opposite to the usual use of the word limit, which means something like “limitation”, as in “the limits of my strength”, or “the limits of my language are the limits of my world”. When I say that reality is a limit, I mean it in the mathematical sense, by which there is an infinite sequence which is trying to reach this limit—reality. This sequence can be thought of as a sequence of physical theories, each better than the previous one, or more broadly, as a sequence of scientific knowledge, growing every day with new publications, or as a sequence of philosophical knowledge, or even as an artistic sequence containing different perspectives on the question “What is reality?” As a matter of fact, any tool to tackle this question is valid. (Except for religion, which puts a ceiling to what can be known, and thus gives rise to a finite sequence—in this case, we are not at the beginning of infinity). What is more: I believe that a question as fundamental and fascinating as “What is reality?” can only be tackled from the multiplicity of perspectives and methods. To get closer to the marvels of reality we must employ science, art and philosophy.

In the remaining, I would like to explain a paradox, which a priori limits (in the usual sense of the word) what can be learned and formalized. I believe that understanding the reach of this paradox is important for our journey to the limit (in the mathematical sense).

It is the liar paradox. If I say “I am a liar” and you ought to decide whether I am lying or not, you will conclude that I am lying if and only if I am not lying—a contradiction. Usually we don’t accept contradictions, so we instead conclude that we cannot decide whether “I am a liar” is true or false—it is undecidable.

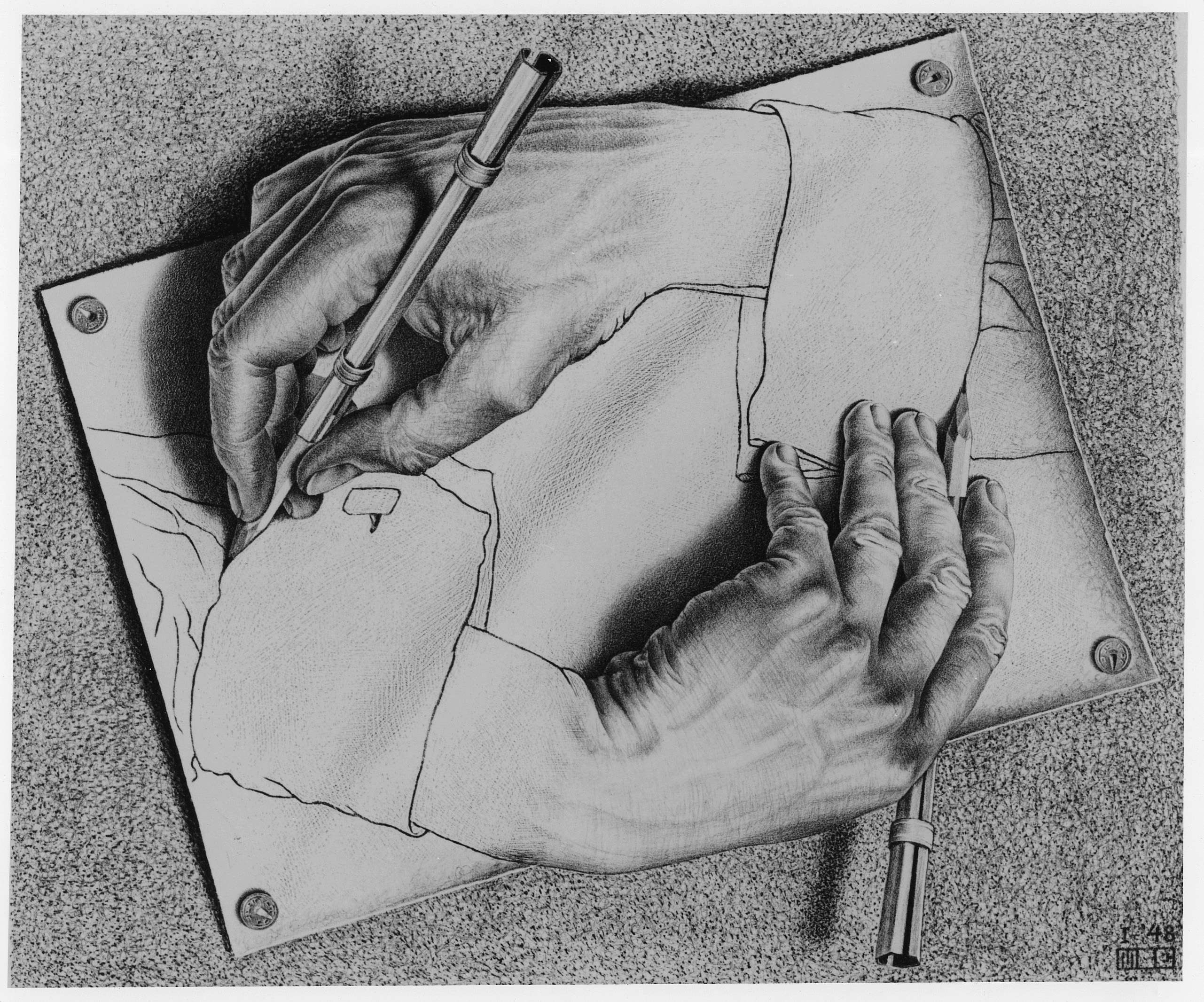

The self-drawing hands of M. C. Escher (1948).

The liar paradox can be formulated in many areas. In mathematics, the formula that says “I am not provable” is at the heart of Gödel’s Theorem, which has very deep consequences concerning what cannot be proven. In computer science, no program can decide whether another program will halt on a given input, or will get stuck in an endless loop—this is the famous halting problem—, precisely because if this program existed, it could take its own description and negate the result, so that it halts if and only if it doesn’t halt. To avoid this contradiction we conclude that the initial program cannot exist, meaning that the halting problem cannot be solved, i.e., it is uncomputable. These examples are not isolated, but quite the opposite: Essentially all functions are uncomputable. In set theory, the set of all sets that do not contain themselves is problematic, because it contains itself if and only if it does not contain itself—this is Russell’s paradox. This implies that the notion of set is ill-defined, as I said at the beginning, which is worrying and surprising, given that set theory is at the base of 20th century mathematics. In epistemology, “this sentence cannot be known”, etc, etc—they are all reincarnations of the liar paradox. Every system that can express self-reference and negation is bound to the consequences of the liar paradox—and expressing self-reference and negation isn’t much to ask, as essentially every non-trivial system can do it.

A graphical example of the paradox are Escher’s hands above. The paradox is resolved because we are outside the drawing—in the words of Hofstadter in Gödel, Escher, Bach, we are at a different hierarchical level than the hands. The liar paradox is like being trapped inside the drawing. The contradiction is usually resolved by postulating that certain things cannot exist—such as a hand that draws another one, which draws the first one.

Moreover, the liar paradox cannot be easily solved. If one decrees “I am a liar” to be true, one can formulate a new sentence which is true if and only if it is false.The liar paradox can only be solved in a limit (in the mathematical sense), usually by building a hierarchy where every level can only refer to the previous level, so as to avoid self-reference. The expressivity of the original system is recovered in the limit of infinitely many levels. Since the limit (in the mathematical sense) is not a physical concept, but only a mathematical one, I do not find this solution satisfactory.

Marcello Mastroianni in 8 1/2 by Federico Fellini (1963). ©Alamy Foto de stock.

Curiously, our minds can understand the liar paradox—you have understood the previous text, and you exist :) Take the movie 8 1/2 from Federico Fellini, where Marcello Mastroianni (image above) engages in a constant exercise of self-reference, directing and participating in the movie, casting characters that appear as actresses and actors in the same movie. Why is the mind capable of understanding self-reference? Essentially, because when I claim that I am liar and then reflect on the truth of this statement, I refer to the Gemma of two seconds ago, which is not the same as the Gemma of this very moment. So I extend the paradox in time. Moreover I can exit the loop “I lie”—“I don’t lie”—“I lie”—“I don’t lie” because of external stimuli. In summary, formal systems have a limitation that our minds, and consequently art, do not have.

While the liar paradox and its many reincarnations is well-established in mathematics and computer science, its importance in physics has been historically neglected. One of the goals of our research group is to understand the importance of undecidability in physics, as well as that of universality, which I believe are intimately connected. I believe that both universality and undecidability are important pieces in our adventure toward that unreachable thing we call reality—or at least important now, or at least worth investigating now. I also think that these concepts are so wonderful and far-reaching that they ought to be explored together with art and philosophy. (I am writing a book called “The zippers of reality” which is a journey at the intersection of physics, philosophy and poetry.)

Going full circle, I do not know what reality is, but I know that thinking about these topics is a dream come true—a dream come real, I am tempted to say, but that would seem to imply that I know what reality is, and that is very, very far from reality.